*Spoilers will be discussed*

Few would have expected a sequel to Joker (2019), exactly 5 years later. The main reason comes down to the fact that it genuinely seemed as if there would be strictly a stand-alone movie, approaching the figure of the villain far more differently than any superhero blockbuster. Todd Phillips’ Joker brought on-stage a seemingly ordinary man, but with a far less typical life, given the burden he’s had to carry since forever. Arthur Fleck, the protagonist, was shown to be falling deeper into madness, as a result of abject circumstances, both back home and in a crumbling Gotham City from the 80s. The latest version of Joker was, consequently, the “product” of a miserable childhood, an aggravated mental illness and a society that would mostly turn a blind eye to individuals similar to Arthur.

Those familiar with the first film would, perhaps, attest to the idea that the story had an impactful message and provided a well-thought-out and self-enclosed world. And yet, none of this prevented the director from providing a follow-up, initially advertised through pictures that would come close to La La Land posters and shots. As unconventional as Joaquin Phoenix’s Joker happened to be, him posing in a dance sequence alongside Lady Gaga truly seemed to be a stretch or straight out of a piece of alternative-universe fanfiction.

On top of that, the movie was also advertised as a musical, further stirring up the internet and having some wonder whether this is the folly that Joker was talking about, in the first film: “I used to think that my life was a tragedy, but now I realize it’s a f---ing comedy.”

Knowing about the musical side of the movie beforehand, I was set on paying attention to details that might ensure a smoother introduction of this genre. An example of one such detail is to be detected when Arthur poetically states that he remembers the music from the night when he killed Murray Franklin. This harks back to a scene, at the end of the 2019 film, where Joker briefly dances to a tune in his own mind, while a massive crowd behind him cheers for him. Earlier instances of Joker dancing are present (and have been far better remembered by the audience); one occurs shortly after Arthur is bullied by 3 people, kills them (out of his total of 6), anxiously hides in a public bathroom, but proceeds to dance there, as a way of reconciling with his deed and letting “the Joker” out. The other scene is the most famous one to emerge from the movie, showcasing Arthur fully dressed up as Joker for the first time and delivering a liberating performance on a stairway near his house.

Despite these acts and Joker’s connection to music, it is not fully convincing that such elements could have properly laid the foundation for an upcoming musical. As expected, singing sections should have the purpose of communicating more than mere dialogue can. In this new production, however, the only time when outward music ends up working is when inmates at the Arkham State Hospital cheer and sing Oh, When the Saints, in hopes of a brighter or a more redeeming future for those like them. (A particularly touching moment is when a young inmate stands up on a table and blurts out the lyrics while looking at Arthur, as prison officers try to take him down – a scene personally reminiscent of the ending to Dead Poets Society, when students loyal to Robin Williams’ Mr. Keating also stand up on their desks and salute their teacher with “O Captain, my Captain!”, from Walt Whitman’s poem holding the same name.) Resuming, I specifically used “outward music” earlier on so as to suggest a contrast, in fact; belted-out songs surely weren’t needed in the first place, for only the inward music mattered all along – that is, whatever was going on in Joker’s mind.

Admittedly, this is slightly taken care of, to a certain extent, by suggesting how plenty of the film’s musical numbers do pan out in Joker’s head. There is much emphasis on this exclusive access to the protagonist’s inner performances, as if the audience members can finally tune into what he has to say or how he wants situations to actually unfold. Truth be told, it is no surprise that the characters and the real-life viewers are all part of Joker’s show – as he pops up in whatever role he might choose (comedian, singer, dancer, lawyer). It is almost as if people wish to witness an entertainer or, in some cases, a martyr that (unwillingly) stands for collective rebellion.

This leads us to the one aspect of the movie that deserves some recognition. The charm never fully rests with the interactions between Joker and Lady Gaga’s severely underdeveloped Harley Quinn, or with their performances together (although the settings of these occasional shows may sit well with some people). The folie à deux in the movie’s title finds its source of power not in the heavily promoted affair between the previously mentioned characters; we might just (re)stumble upon the manic tango between none other than Arthur and Joker, a dance that has been there from the start. This duality has some characters believe that there can be a case of a split personality or a dissociative identity disorder, thus having Joker be the one responsible for all the past crimes; as a result, a trial awaits Arthur and takes centre stage for the most part.

What is worth noticing, throughout the entire film, is how there are multiple shots of the protagonist as seen on camera, either during interviews or in the courtroom, with the trial broadcast live.

This focus on cameras can have one wonder about the nature of these videos and how you could generally make use of them. The answer depends on who the subject of interest is; should the focus be on Arthur, we would be provided with valuable footage for a possible case study, with the recordings holding testimonial value, to a certain extent, as they also capture the man’s body language and long breaks before he begins to talk. With Joker, on the other hand, there would be an underlying inclination towards drama instigation and foul entertainment, igniting intense riots, with people using the “jester” as a symbol of anarchy, chaos and a dangerous kind of freedom. In this respect, a short scene with Harley Quinn may stand out, where she nonchalantly steals a small TV, from a shop, and carries it away, as it keeps showing Arthur, after he has serenaded her on national TV. The shot is representative, with Arthur’s face on the screen and the suggestion of him being “entrapped” in a TV set, simply carried around as a symbol of rebellion against authorities, but barely acknowledged solely as the person behind the “clown mask.”

Arthur’s retreat into fantasy has been evident since the 2019 movie; the difference, this time around, is the fact that he is granted multiple instances “under the spotlight,” under the gaze of countless individuals. Wherever he finds himself, he also refashions his mental diversions according to his surroundings, as a kind of coping mechanism for when he’s not in control of the real-life situations. One of his fantasies even presents him shooting the cameras in the courtroom, interrupting the broadcast (and refusing further shooting “on set”). In reality, much of the film’s tension is between Arthur “being himself” and the overall act of “giving the people what they want.” The story gradually reveals that no fervent fan of Joker would be equally interested in Arthur Fleck, as the latter remains unknown (or forgotten) in the public eye – and this is something expressed in a joke told by Arthur, its classic structure missing a line, but definitely not the punch: “Knock, knock! / Who’s there? / Arthur Fleck. / Arthur Fleck who?”

It would be amusing to ever find out that the objective with Harley Quinn was only to divert the viewers’ attention from the real deal, have the actual meaning of folie à deux come forward as a plot twist. However, this might not ever be the case and it most definitely leaves most of the audience puzzled with Harley’s purpose in the story. Indeed, despite her lacking substance, she is still a representative of those that are devoted to Joker, but who end up taking steps back when they hear that their “hero” never existed. This is precisely Arthur’s declaration in his closing statement, during the trial, as he renounces his alter ego and decides to take full responsibility for his crimes and, implicitly, his dark side. It is a matter of coming to terms with one’s Shadow, which is to be understood from a Jungian perspective, as the Shadow refers to repression, the act of hiding anything that is detrimental or unacceptable at a social level. Admittedly, in Arthur’s case, his hidden part does come to light through Joker, but, all the while, he also manages to keep issues at bay through this persona and ensuing fantasies. A medical diagnosis, backed up by childhood trauma, would grant him special care in an institution, but Arthur still opts for a different path (and has his expectations crushed in no time, when Harley turns her back on him).

Nevertheless, the protagonist’s public confession could be said to make sense in the overall scheme of events. Retrospectively, viewers could link it to the short animation that opens the movie, Looney Tunes-esque (the franchise and the Joker films being distributed by the same studio, Warner Bros.). The cartoon is entitled Me and My Shadow, featuring Joker and his actual shadow fighting for the star position. The latter temporarily wins the quarrel and briefly performs on the Murray Franklin Show, but as soon as policemen step into the picture, it abandons the body it inhabited, leaving the figure of Joker (who is actually the vulnerable Arthur) in the hands of the merciless officers. The animation is one of the best aspects of the film (if not the strongest), as it emphasizes a recurring image. In the 2019 production, Joker was the face of a rebellion and his symbolic shadow was represented by the waves of protesters behind him.

In Folie à Deux, the roles are reversed, as Joker slowly “transitions” back into Arthur and steps away from the spotlight, in more ways than one. Even towards the end of the film, his drab clothing accentuates his shadowy appearance and, additionally, he can be seen running away from a protester who perfectly resembles Joker, in his colourful demeanour.

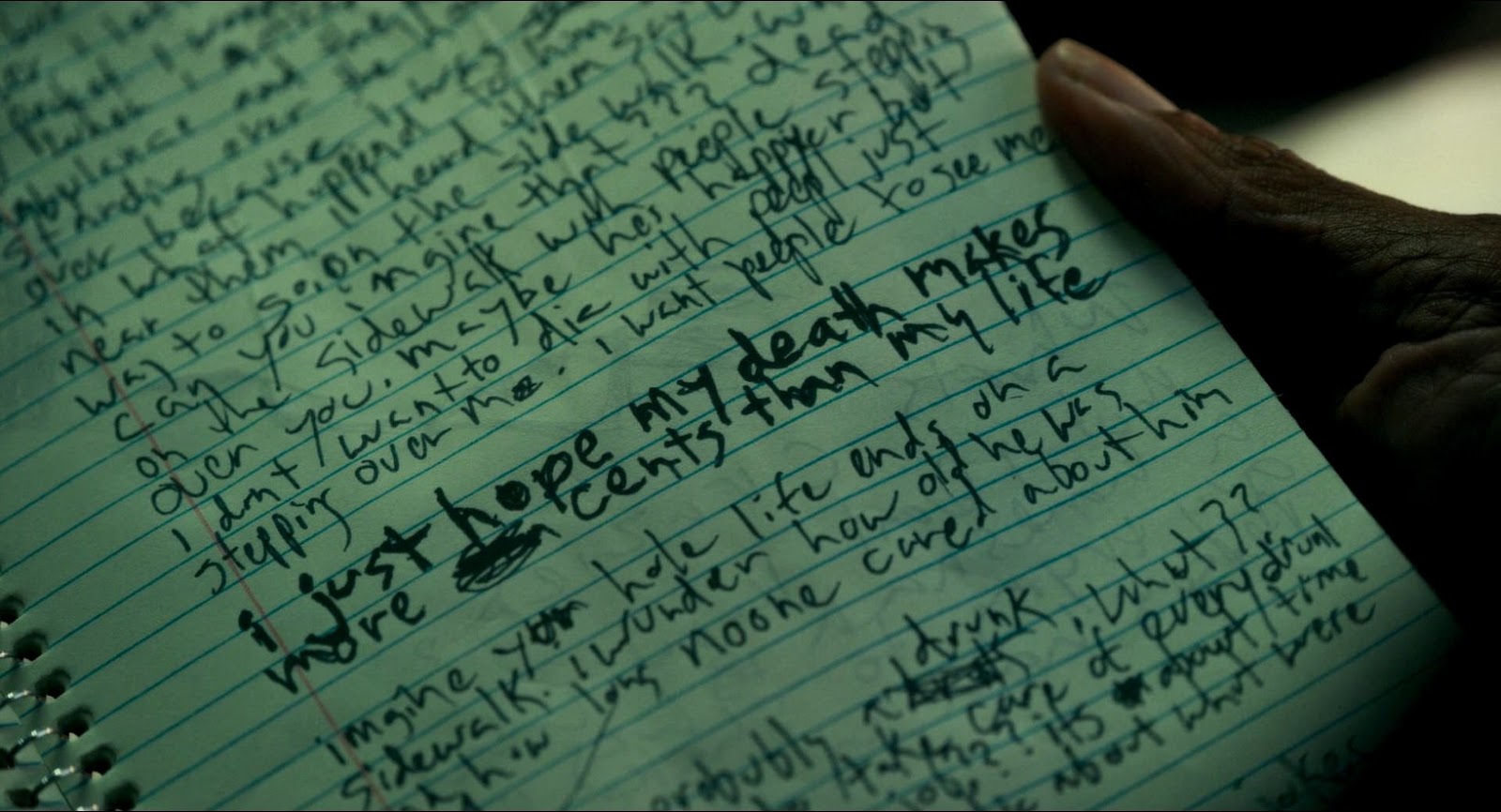

It can become quite tiring to understand why Joker 2 has been invested in its musical side, after all. Either way, willingly or not, the director has also shown what it is like for Arthur to distance himself from any movement associated with him and reach some sort of inner peace (if it can be deemed as such), once he annihilates his personal, fictive Joker. However, little does he know that his legacy will never die out, since the folie continues to be shared. In this sombre atmosphere, one of Arthur’s remarks, written in his diary, in the first movie, rings in the air: “I just hope my death makes more cents than my life” (presumably “cents” replacing “sense”).

Given the second film’s lower success at the box office, there is not much hope when it comes to the financial aspect. As for the meaning behind the whole endeavour, it comes down to the viewers hanging onto worthwhile elements of the story – and asking themselves the right questions. For maybe the Joker’s shadow is at work – but can Arthur effectively undergo some shadow work? Maybe entertainment and Joker’s allure and shtick invited the audience into his world – but how many people will stick around for Arthur’s final act?

Comments

Post a Comment