“ ‘He’s writing his name in water,’ I said.

‘What’s that?’

It was the half-regretful term – borrowed from the headstone of John Keats – that Crabtree used to describe his own and others’ failure to express a literary gift through any actual writing on paper. Some of them, he said, just told lies; others wove plots out of the gnarls and elf knots of their lives and then followed them through to resolution. That had always been Crabtree’s chosen genre – thinking his way into an attractive disaster and then attempting to talk his way out, leaving no record and nothing to show for his efforts but a reckless reputation…” (page 93)

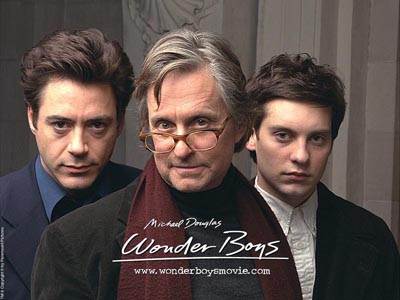

With that being said, we are subtly introduced to the entire notion of being a “wonder boy”, a person who achieves success effortlessly and doesn’t have the ability to either analyze their talent or replicate it. Wonder Boys’ author, Michael Chabon, presents one such unfolding path through the eyes of a writer who has just passed his own experience onto the main character and can unashamedly joke at his own expense in a similarly heartbreaking and ironic manner. Concurrently, Wonder Boys’ director, Curtis Hanson, preserves the general ambience, introduces his small but witty alterations and reminds the audience – in an exclusive interview – that “wonder boys” can be found in any context.

The plot follows Grady Tripp – a novelist and a Creative Writing professor at an arts college in Pittsburgh – throughout the course of an eventful weekend. He gets tangled up in a pile of mess involving his wife’s definite departure, his girlfriend’s pregnancy confession, a dead dog, a stolen Marilyn Monroe jacket and a car stalker. Meanwhile, Grady forms an unexpected bond with one of his students, James Leer, a damaged individual, not adapted to social contexts, but incredibly gifted with words, being capable to produce gripping stories in a short amount of time. To have the atmosphere properly stirred up, Tripp’s editor, Terry Crabtree, also comes into town and attends the university’s literary conference, WordFest, as a pretext for his wish to look over Grady’s latest novel, (un)surprisingly entitled Wonder Boys. These external conjunctions ignite insupportable internal concussions, oppressed in the initial stage, but eventually requiring Professor Tripp to take control… and make choices.

One’s perception of characters can be different, depending on whether they choose to read the book or watch the movie first. Should someone discover Wonder Boys via the 2000 film, they will most likely end up feeling at peace with the development. On the other hand, the novel will have its newbies gawping at countless authentic, moderately detailed paragraphs and perhaps wishing to hear more from the protagonist. It may actually be advisable for people to start off the journey with the book. Afterwards, the movie will help them observe the director’s freedom of combining scenes and adding clever segments, simultaneously remaining true to the author’s plain intentions.

The “aura of independence” may be first spotted at Terry Crabtree. In the book, he seems to be a desperate editor marching at the same pace as his old friend, Grady. However, on the screen, he puts on the highly deserved show, diverging from the hopeless path and indicating more clearly he can be full of surprises if he’s offered the much needed spark. Tempting with his facial expressions and confusing with his sudden mood switches, Robert Downey Jr’s Crabtree is finally seen standing on his own two feet, knows what could be going on behind his back and startles James with his serpentine alluring actions. Everyone’s in for a treat, that’s for sure.

As the editor is left searching for his upcoming hit to publish, young James Leer may turn heads, for his shyness and gloomy issues don’t mark an inauspicious future. His bundle of lies, naturally constructed, can’t make anyone angry, but rather perplexed, eager to witness the student’s muddled walk. James, skillfully played by Tobey Maguire, often hears harsh commentary from surrounding voices, with concomitant questions such as, Is your reality made up of false stories? Or are your stories inspired from reality? Michael Chabon doesn’t fully motivate the boy’s attitude resembling an “alien probe”. His character can laugh at anything for whatever reason and be as solitary as he desires. In the movie, though, there are two key scenes which introduce new perspectives.

Q.’s petty speech, Y tryin’ to teach?

At WordFest, a writer recurrently known as Q. holds a lecture in a full auditorium. Chabon and Hanson go for separate speech topics, both of them leaving Grady and James baffled and bored. In the novel, the atmosphere is narrated passively by a drunk Grady “having a tough time concentrating on his words”. The main theme is briefly mentioned, the reader is not supposed to pay a lot of attention to this aspect.

“It seems to me that Q. was talking about the nature of the midnight disease, which started as a simple feeling of disconnection from other people, an inability to ‘fit in’ by no means unique to writers (…). Very quickly, though, what happened with the midnight disease was that you began actually to crave this feeling of apartness, to cultivate and even flourish within it. You pushed yourself farther and farther and farther apart until one black day you woke to discover that you yourself had become the chief object of your own hostile gaze.” (page 76)

The abrupt element is James’ laugh in a still environment, a laugh “out loud, at some private witticism that had bubbled up from the bottom of his brain”. The reader is not certain whether he has found something foolish in Q.’s words or has thought of something completely unrelated. In the movie, Curtis Hanson has decided to contextualize the bizzare burst, therefore the entire auditorium holds James’ echoing laugh immediately after Q. states the following:

“I am a writer. As a writer, you learn that everyone you meet has a story. Every bartender, every taxi driver has an idea that would make a great book. Presumably, each of you has an idea. But how do you get from there to here? What is the bridge from the water’s edge of inspiration to the far shore of accomplishment?”

The cryptic student may slightly become more relatable, viewers finally detecting his disapproval of Q.’s foolishly nonchalant stance. This qualifies as one of the most important insights into James’ mentality.

Style the writing, pile the emotions!

The boy’s world is once again intruded into when Grady and Terry go to James’ house. The real “break-in” occurs when the two friends come across his compositions. Chabon builds up a somewhat envious Tripp who reads James’ work and later admits sincerely he may begin to lose Crabtree when the student takes his place as the new promising writer:

“At the sight of James in Crabtree’s jacket I experienced a sharp pang of abandonment (…). I guess you could say that in a strange sort of way I’d always believed that Crabtree was my man, and I was his. It was only proper, I supposed, for the first thing in my life that had ever felt right to be the last one to be proven wrong.” (page 338)

Hanson seeks to transform the professor-student connection into something even more special and remind everyone that Grady has inspired his faithful student to write in the first place. Thus, the director gives Terry the significant job to find a paragraph written by James, which features an emotional apprehension based on a recent real-life interaction (the most honest words so far, given the boy’s lies and messed-up perceptions):

“Terry: Hey. Check this out. ‘Finally, the door opened. It was a shock to see him shuffling into the room like an aging prizefighter. Limping. Beaten.’ Does that sound like anyone we know? ‘But it was later, when the great man squinted into the bitter glow of twilight…’ ‘Twilight’, this kid definitely needs an editor. ‘… and muttered simply, “It means nothing. All of it. Nothing.” that the true shock came. It was then that the boy understood that his hero’s true injuries lay in a darker place. His heart, once capable of inspiring others so completely, could no longer inspire so much as itself. It beat now only out of habit. It beat now only because it could.’ ”

James is never meant to be Grady’s competition. The troubled teacher has no other option than to admit he struggles with writer’s block (hence his never-ending novel) in a delirious trance. Michael Douglas’ Grady Tripp is once and for all under the spotlight and has one unique mission in each medium. Within Michael Chabon’s pages, he explains himself to his loved ones (including Emily, his former wife, who doesn’t even appear in the movie), reconsiders his actions, learns to take mature decisions (for writers make the most choices, after all) and declares he’s had a worthwhile impact on his students, despite his pestering issues from the last couple of years. In Curtis Hanson’s eyes, he sticks to the same principle, but he also subconsciously connects to James a whole lot more. Chabon almost presents Professor Tripp as being left out for a while, perhaps even forgotten by the young student, which would come off as an unfair move.

Reconciliation is sought (and found) in many places and it’s truthfully felt in one last touching scene. Overall, Grady has to come to terms with his evolution and that happens symbolically when James’ novel, Love Parade, gets published. In the movie, in a packed auditorium, the teacher has the opportunity to proudly shout, Take a bow, James! (contrary to the book, in which another fellow student says that), and oficially “initiate” his apprentice into the world of admirable accomplishments and reasonable failures by passing on the wondrous title of “wonder boy”.

It wouldn’t be fair to point out that Curtis Hanson did a better job than Michael Chabon or vice versa. Both universes are to be praised for their distinct approaches. The author clearly prefered to tread behind Grady and guide him through twisted encounters, whereas the director felt the need to illustrate all three wonder boys equally. Readers and viewers altogether will distinguish the common trait: we’re all wonder figures in our own ways, with temporary sadness rooted in our suspicions, but permanent hope concealed in our redefinitions.

Comments

Post a Comment